The Case for Niger

Why the World’s Most Overlooked Uranium Basin May Hold the Key to the Nuclear Future

The uranium market suffers from a profound crisis of imagination. Yield-hungry institutional funds, desperate for exposure to the nuclear renaissance, have funneled billions into mature basins where the odds of meaningful new discoveries have long since collapsed. This fixation on what might be called “jurisdiction-first” investing—prioritizing political comfort over geological promise—has created a systemic discovery deficit that threatens to leave enormous value on the table.

The Athabasca Basin remains a technical marvel, home to some of the highest-grade uranium deposits ever found. But its maturity masks a troubling reality: the easy discoveries have been made. For every success story, there are dozens of failed programs, each representing tens of millions in squandered capital. The basin has become a crowded casino where the house odds grow worse each year.

Meanwhile, in the Sahara’s southern reaches, an extraordinary geological system sits almost entirely unexplored by modern standards. The Aïr-Tim Mersoï Complex in Niger, a region that has quietly produced uranium for over half a century, represents what may be the world’s most fertile ground for discovery. For investors willing to see past headlines about coups and Saharan instability, it offers something increasingly rare: genuine asymmetric upside.

The Mathematics of Discovery

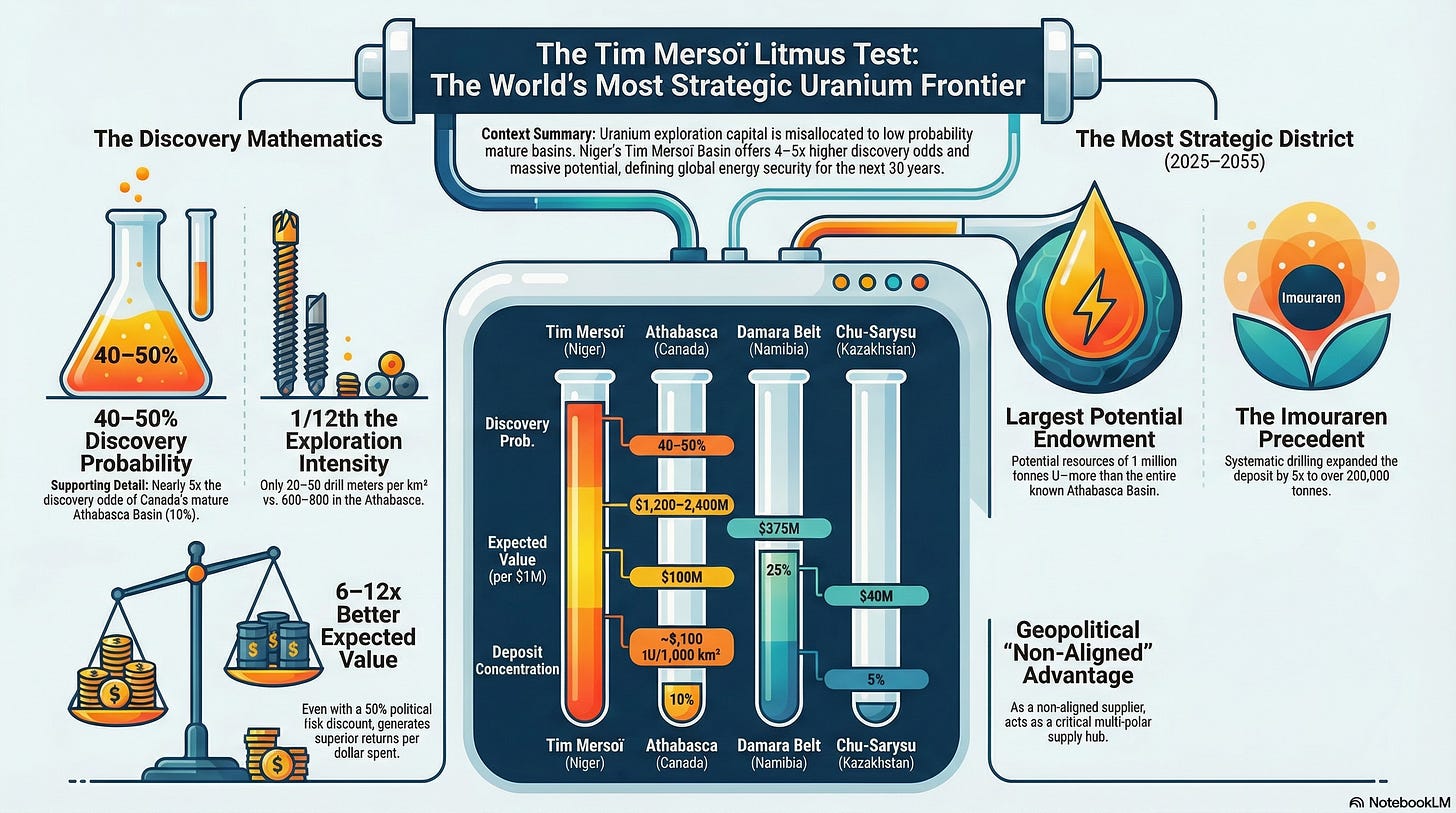

Strip away the noise of political risk assessments, and what remains is simple arithmetic. Discovery probability multiplied by potential scale equals expected value, the only metric that ultimately matters for exploration capital. When you run the numbers, the results are striking.

In Tim Mersoï’s northern extensions, the discovery probability ranges from 40 to 50 percent. The Athabasca, by contrast, offers roughly ten percent. This isn’t conjecture; it reflects the geological fertility of sedimentary systems where uranium-rich fluids have concentrated over hundreds of millions of years. The Carboniferous and Permian sandstones of Niger host the same mineralizing processes that created the world’s great deposits, but they haven’t been drilled.

The average deposit in Tim Mersoï runs between sixty and one hundred thousand tonnes of contained uranium. Canadian discoveries typically yield thirty to fifty thousand tonnes. Even accounting for Niger’s challenging operating environment, the expected value per exploration dollar spent in the Akokan-Teguidda district dwarfs anything available in North America or Namibia. It outperforms even Kazakhstan, the world’s dominant producer, by a factor of thirty or more.

The Coward’s Excuse

Sophisticated investors understand the difference between headline risk and mathematical risk. The 2023 coup in Niger sent tremors through boardrooms from Toronto to Perth, and institutional capital retreated predictably. But this conflates two distinct phenomena: political uncertainty and exploration probability.

Apply the most punishing stress test imaginable, a fifty percent discount to account for every conceivable political nightmare, and the Tim Mersoï still delivers six to twelve times the expected value of the Athabasca’s best-case scenario. It remains nearly twice as attractive as Namibia’s Damara Belt, widely considered the industry’s most investor-friendly African jurisdiction.

This is sovereign risk arbitrage in its purest form. The concentration of capital in “safe” zones ensures mediocre returns while geological reality goes unexploited. In an era of structural uranium supply deficits, when every utility scrambles for long-term contracts, and spot prices climb relentlessly, the true risk isn’t Niger’s politics. It’s the mathematical certainty of low-probability failure in the crowded basins of the West.

The Exploration Gap

The numbers tell a story of deliberate neglect. The Athabasca Basin has been drilled at densities of six hundred to eight hundred meters per square kilometer, a geological sponge wrung nearly dry. The Akokan-Teguidda district has seen perhaps twenty to fifty meters per square kilometer. This isn’t a market failure; it’s a legacy of strategic suppression.

For decades, French interests, first the Commissariat à l’énergie atomique, later Areva and Orano, maintained Niger’s reserves as a kind of geological savings account, extracting what was needed while keeping the broader system “on ice” for future development. The information asymmetry this created persists today, leaving vast swaths of prospective ground unexplored by modern standards.

The Imouraren deposit offers a preview of what systematic exploration might reveal. When serious drilling finally commenced between 2004 and 2012, the resource expanded from a 1960s estimate of forty thousand tonnes to a staggering one hundred ninety thousand tonnes, nearly a fivefold increase from the application of modern techniques to ground that had been neglected for half a century. The same Tarat sandstones and Guezouman formations that host Imouraren extend one hundred fifty kilometers north into virtually untouched terrain.

Separating the Serious from the Zombies

The junior mining sector has become a graveyard of missed opportunities. Too many companies exist not to find minerals but to extract management fees, entities that deploy shareholder capital on Toronto office space and marketing consultants while the drill bit gathers dust. These firms hide behind “tier-one jurisdiction” narratives, offering political comfort in place of geological results.

The tell is in the allocation. Companies spending less than forty percent of their budgets on actual drilling are not serious exploration ventures; they are salary extraction vehicles dressed in mining company clothing. The genuine discovery players, vanishingly rare in today’s market, can articulate a quantified expected value analysis and back it with aggressive exploration spend.

Meanwhile, China has noticed what Western investors refuse to see. State-owned enterprises like CNNC and CGN have quietly positioned themselves across African uranium districts, including Niger, while Western juniors congratulate themselves on their prudent risk management. The strategic implications of this capital flow are difficult to overstate.

The Unavoidable Truth

The Tim Mersoï Basin possesses the highest deposit concentration on Earth, somewhere between seven thousand and eight thousand tonnes of uranium per thousand square kilometers. Its potential endowment may exceed one million tonnes, a figure that dwarfs the known resources of the entire Canadian shield. For the 2025 to 2055 investment horizon, this region represents the geopolitical fault line of the nuclear energy transition.

Every institutional manager with uranium exposure should be asking uncomfortable questions. What is the mathematical justification for accepting four to five times lower discovery probabilities in “safe” jurisdictions? What is the quantified cost per expected tonne discovered? Is the portfolio positioned for actual discovery or merely for the appearance of prudent resource exposure?

Avoiding Niger is not a mark of prudence. It is a choice to accept sub-par returns while a genuine opportunity passes into other hands. In the coming decades, the geopolitics of energy security will be shaped in meaningful part by who controls Tim Mersoï’s riches. Those who ignore this reality are not managing risk—they are choosing irrelevance.